|

MAY 2017

|

69

THINK

shoes, gasoline, food, cars and

trucks. The BAT tax would affect

imports from every country,

including free trade agreement

partners. No exceptions.

Let’s see how this works

in practice with an overly

simplified example.

Suppose you import

promotional backpacks at an

average import cost of $10. You

pay $1.76 in tariffs (17.6 percent

rate) and overhead—including

costs of embroidery in the U.S.—

of $8.74. Your unit sale price is

$21.51, netting a pre-tax profit

of $1.01 and a tax bill (at a rate of

35 percent) of 35 cents.

Under the BAT, the math

changes significantly. Your

corporate tax rate now drops to

20 percent, which is fantastic. But

that lower rate now taxes a much

higher base—your profit

and

the price you pay to import the

backpack

and

the tariff you pay

when you import the backpack.

That’s right, you pay an income

tax on the tariff. Now your total

income tax bill explodes to $2.55,

which is seven times the amount

you paid before and now means

you’re paying an effective tax rate

of 255 percent.

Gulp!

Clearly, you can’t run a business

when the government taxes more

than 250 percent of your profits.

So you will try to pass these costs

along—in the formof higher

prices. But this may not work in a

price-sensitive industry such as

ours, as higher prices may force

customers to choose a less-taxed

advertisingmedium (print or radio

perhaps), lower the number of

items purchased or choose less

expensive promotional products.

You could try to cut overhead, but

don’t forget that your other costs—

such as energy—are also going to

increase since everybody else in

the economy will also face their

own inflationary pressures due to

the BAT.

Proponents tell us that this

won’t happen. They argue that

the BAT will instantaneously

cause a substantial increase

in the value of the U.S. dollar,

immediately lowering the cost

of imports, which would shield

importers (and their consumers)

from cost increases. Yet that

scenario—based on a theory

that even economists can’t agree

upon—provides cold comfort.

Most import transactions, and

certainly nearly all those in the

promotional products industry,

are denominated in dollars.

Moreover, currency rates are

affected bymany, manymore

factors besides trade flows. So the

thought that (a) an exchange rate

change would happen; (b) if it did,

it would happen instantaneously;

or (c) that such changes would

enable contracts to be easily re-

negotiated is pure fantasy.

Proponents also argue that

the BAT is needed to align U.S.

tax policy with that of other

countries. They point to the

system of value added taxes

(VAT) that other countries use to

conjure up an imaginary “Made

in America” tax. Those VATs

are

imposed on imports

from

the United States (and other

countries) and are

rebated on

exports

to the United States (and

other countries). Since these

VATs are border-adjusted—so

goes their logic—it is only fair

for the U.S. to do the same. What

they fail to mention is that those

VATs are border-adjusted sales

taxes, while the House-proposed

BAT would border adjust the U.S.

corporate income tax.

Moreover, if the U.S. succeeds

in doing this, it would be the only

country that is border adjusting

its income tax.

To make matters worse,

enactment of the BAT could

easily trigger a tax and trade war,

as our trading partners retaliate

by imposing countervailing

measures. Some have already

threatened to do so. In the longer

term, the U.S. is likely to see a

challenge in the World Trade

Organization (WTO), since this

plan would appear to violate

several key WTO principles. If

successful, a WTO challenge

would enable other countries to

legally impose punitive tariffs on

U.S. exports—to the tune of $385

billion, according to an estimate

by the Peterson Institute for

International Economics.

It’s no wonder small and large

businesses alike feel the BAT is

an existential threat. A coalition

of more than 400 businesses and

trade associations, including

PPAI and the American Apparel

& Footwear Association (AAFA),

have come together under

the banner of Americans for

Affordable Products (AAP) to push

for comprehensive tax reform that

does not contain the BAT.

So what happens next?

House Republicans expect to

publish details of their tax plan

before summer, while Senate

Republicans, who have expressed

concerns over the BAT, are actively

exploring other options.The

Congressional leadership, along

with theWhite House, has labeled

tax reforma priority andmost

experts agree that some formof

tax reformcan get approved by

this Congress. It’s beenmore than

30 years since the last significant

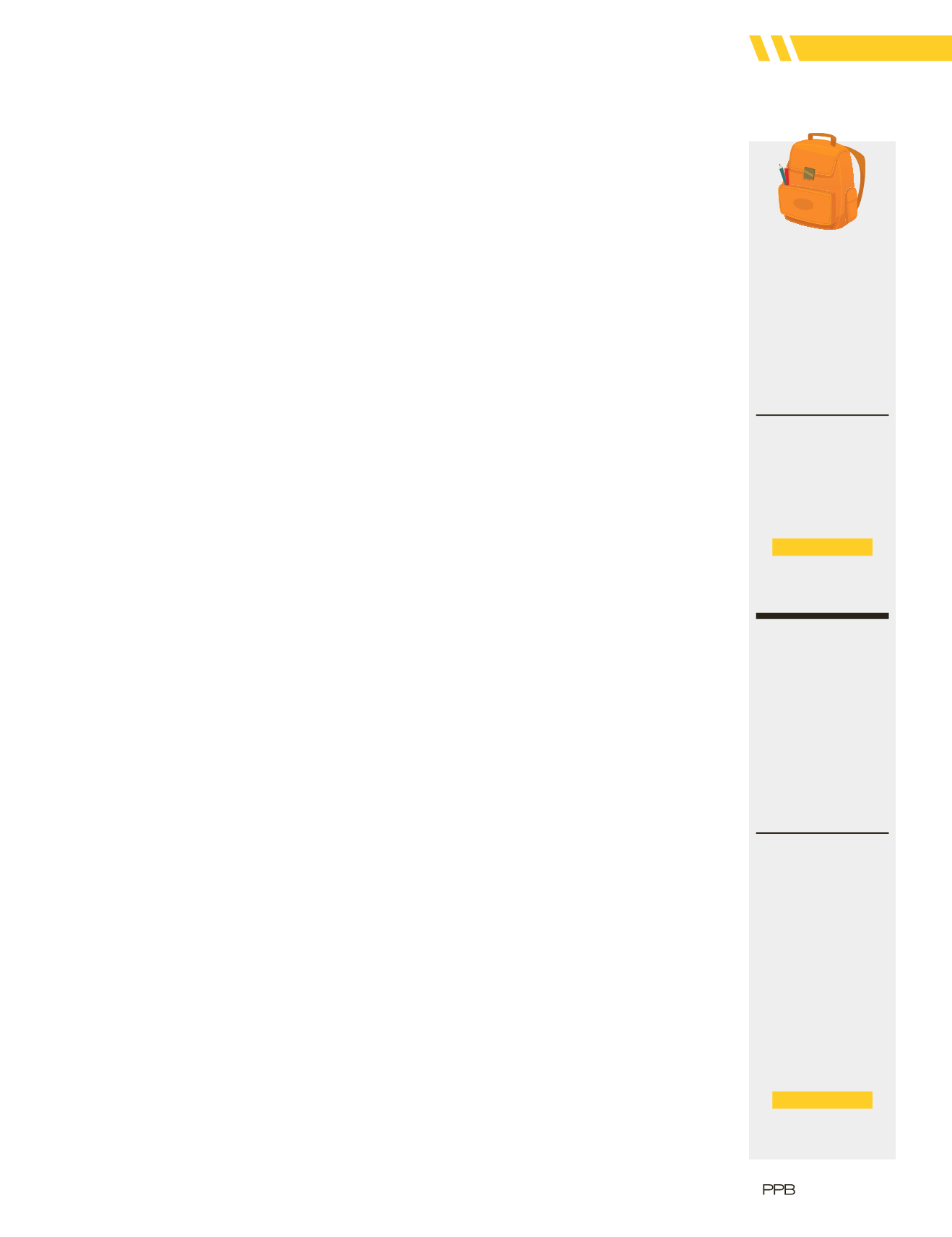

Current Scenario

$10

(average import cost)

+

$1.76

(duties at 17.6% tariff rate)

+

$8.74

(overhead, including

embroidery)

$20.50

total cost

Sale price:

$21.51

Pre-tax profit:

$1.01

Income taxes paid:

$0.35

After tax profit

$0.66

Under BAT

Proposal

$10

(average import cost)

+

$1.76

(duties at 17.6% tariff rate)

+

$8.74

(overhead, including

embroidery)

$20.50

total cost

Sale price:

$21.51

Pre-tax profit:

$1.01

Income tax on profit:

$0.20

(20% of profit)

Border adjusted tax on

import cost:

$2

(20% of

import cost)

Border adjusted tax on

duties paid:

$0.35

(20% of

duty paid)

Total tax paid:

$2.55

After tax profit

-$1.54

Two Views Of

A Backpack Sale