|

OCTOBER 2016

|

13

INNOVATE

(aptly named LoudRock Studio

after the kids), and it’s amiracle he

has any time to createmusic.

“In the summer I don’t,” he says.

“I only have time to work onmusic

in the winter months.” Since he lives

and works in the same community,

he goes home for lunch. “I sit down

for fiveminutes and try to come

up with five ideas. Usually I find

two good pieces. You don’t have

to construct a full song—you just

need a strong part and a not-so-

strong part—and it only needs to

be a couple of minutes long. You’re

trying to set amood and a tone, not

be a focal point. If it’s too busy, it

doesn’t work with dialogue,” he says.

One time he set a goal to create

and finish a song in one hour. “And

that thing has been played on TV!”

he says. Hearing his songs on TV is

a thrill, although he rarely catches

them, in part because he has little

time to watch TV. Usually he’ll find

out a song of his has been used only

when he gets his royalty statement.

But once he caught his song in

action on aWeather Channel

show called

Lifeguard

. “They used

my song as themusic that plays

when you go to commercial. I

remembered the show being onmy

royalty statement and when I saw

there were new episodes coming

up, I recorded them.That was the

first time I heardmy song on TV,”

Nokes says.

While writingmusic for TV

isn’t necessarily going to support

a family, movie trailers are a lot

more lucrative. He’s been trying

for a few years to break into that

market. “Unfortunately, it’s highly

competitive andmovie trailer

songs are done on spec [with no

guarantee of being chosen or paid].

On the flip side, if your music gets

chosen, the potential payment

is substantial.”The good news is

that the feedback he’s gotten on

his movie trailer songs has been

positive and helpful. Once summer

is over, he’ll go back down in the

basement, review those critiques

and get to work.

Check out Nokes’ music on his

website at www.carchasemusic.

comor at

https://soundcloud.com/jnokes.

When MTV

came out in the

early ’80s, it

made a lasting

impression. I

thought guitar

was really cool.

So I taught

myself how to

play guitar and

played in bands.

But I always

liked the writing

music portion

of that the best,

rather than

the performing.”

Left, Nokes records

guitar tracks in his

basement studio,

next to the sump

pump and AC unit.

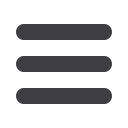

Jason Nokes (left) and David

Shultz, DistributorCentral VP and

member of the triathlon band Iron

Band, show off the guitars given

to them as gifts by supplier Brand

O’ Guitar Company (UPIC: guitar)

at The PPAI Expo 2015.

BehindThe Scenes of TVMusic

Composers:

The creators of

the music.

Publishers:

The organizations

(such as ScoreKeepers Music)

that collect, tag by theme,

market and store composers’

music. “There’s a contract

between the publishers and

the composers. The publishers

have a certain number of

songs of mine and we’ve

already negotiated our rates

and payment. And then the

publishers negotiate between

themselves and the TV shows.

So any time the TV show finds

a song, they don’t have to

negotiate with all those people.

If you look at reality shows,

there is music going on all the

time. They could go through

100 songs in an episode,”

Nokes explains.

Music Supervisors

: The people

in charge of music for a TV

show. Nokes says, “They’ll

have in mind what type of

music they want to use in these

different scenes. They’ll have a

relationship with the publisher

and typically they’ll have full

access to all the songs the

publishers have in their library.”

Performing Rights

Organizations:

Music

supervisors turn in a cue

sheet, which lists all the songs

they used, how much of the

song they used and how

often, to a performing rights

organization. The two biggest

ones are Broadcast Music,

Inc. (BMI) and the American

Society of Composers, Authors

and Publishers (ASCAP). The

performing rights organizations

divvy out the money to the

publishers and the artists. Says

Nokes, “I’ll get music on TV

but I won’t know about it until

months later. It just shows up

on my royalty statement.”

Royalty Statement:

The

document that details what

shows in countries all around

the globe have paid to use a

composer’s songs. Amounts

can range from as little as one

cent to hundreds or thousands

of dollars.

Julie Richie is associate

editor for PPB.